Mullinax, Squirrel Gap, & Poundingmill Trails

And A Reflection on Wilderness…ness

On Saturday, November 14, 2015, my wife and I found ourselves with some free time and a babysitter, so we headed down to the Turkeypen trailhead to do a loop that included one of the few remaining trails in the Pisgah district I hadn’t fully completed yet: Poundingmill trail (#349), which connects the South Mills River trail to the Squirrel Gap trail near Poundingstone Mountain.

In addition to checking this trail off the list, I also wanted to take the opportunity to experience a hike inside an inventoried potential Wilderness area to get some perspective on the Forest Service’s open request for comments on that issue. More on that to come.

Despite having a babysitter, we still didn’t have a ton of time due to the pick-up schedule and another event we had planned for that evening back in town – not to mention the rapidly diminishing light on these late autumn days. We figured we’d be able to squeeze in a 5-6 mile hike, somewhere within about a half hour drive of Asheville.

The loop we chose fit the bill perfectly: starting at the Turkeypen trailhead in the South Mills River area, down the connector to the suspension bridge, up the Mullinax trail to the Squirrel Gap trail, and then down Poundingmill, back to the South Mills River trail to complete the loop.

The forecast was finally calling for some cooler weather despite what had been a very warm autumn up to that point. Only 3 days earlier, temps had gotten up near 80 in the mountains! And that’s after two weeks of temps solidly in the “warm” category – it felt more like September than mid-November. But after what appeared to be a crisp morning and seeing terms like “chilly breeze” in the forecast, we made sure to don a few layers before heading out under a clear blue sky.

Join the Crowd

Despite considerable stop-and-go traffic on I-26, we arrived at the trailhead in plenty of time to finish the hike. Only problem was, there appeared to be no parking spots remaining! It was packed, and starting to look like we wouldn’t get the semi-wilderness hike I had expected.

We finally managed to find an empty piece of ground sort of up on a bank near the trail sign, but it was plenty big enough for my little Suzuki to come to rest out of everyone’s way.

The parking area is split up into two sections, one for horse trailers and one for cars. But don’t even think about nudging over into the horse trailer area if the car lot is full. In fact, on this day, a bright pink line had been spray painted across the middle of the gravel lot by the horse folks, presumably intended to serve as a warning to any wayward parker who may be tempted to ease that direction to find a space.

The Forest Service has talked about improving this situation in the future, though it’s not sure if funds will ever be available to enlarge this lot. The road leading up to it needs some serious work, too.

Nevertheless, once on the trail, we quickly lost the crowds and started enjoying the hush of the forest. Almost immediately, we could begin to hear the rush of the South Mills River down in the valley to our left. Since there had been plenty of rain during the preceding early November warm spell, the river was running pretty high and side streams were flowing heartily. Mud pits were out in full force attacking trouser legs and hiking boots, too.

At the swinging bridge, I stopped briefly to take out my camera and ponder the special area we were about to enter. The mountains around the South Mills River, including the one we were about to hike, lie within the South Mills River backcountry area. And it’s an area being considered for a “promotion” of sorts: to Wilderness.

This Place Has a Plan

I’ll get on with the hike description below, but first a little backstory about why I wanted to hike here this weekend.

The Forest Service is currently undergoing a revision to its official master plan which will set the direction of its forest management activities for at least the next 15 years. It’s A Big Deal. And it has not been a process without controversy. In fact, heated exchanges between the Forest Service and the general public over the nascent plan have been ongoing for at least the past year – and it’s not due to be finished until sometime in 2017.

The Forest Service divides its land up into “Management Areas” – zones, basically – to determine what types of things can or can not be done within sections of the forest, including road-building, logging, habitat restoration, mining, and so on. As it happens with nearly any government zoning proposal, opinions and tempers fly when maps are published showing Your Favorite Place to be within Your Least Favorite Zone.

And that’s exactly what happened before one particularly raucous gathering at the Big Ivy community center earlier this year. Big Ivy is another area of Pisgah National Forest about an hour north of South Mills River area near the community of Barnardsville, NC. The draft proposal was so distasteful to nearby residents and forest users that it ended up launching a group called Friends of Big Ivy and a campaign with bumper stickers proclaiming “Don’t Cut Big Ivy!”.

One of which, by the way, is affixed to the back window of my Suzuki.

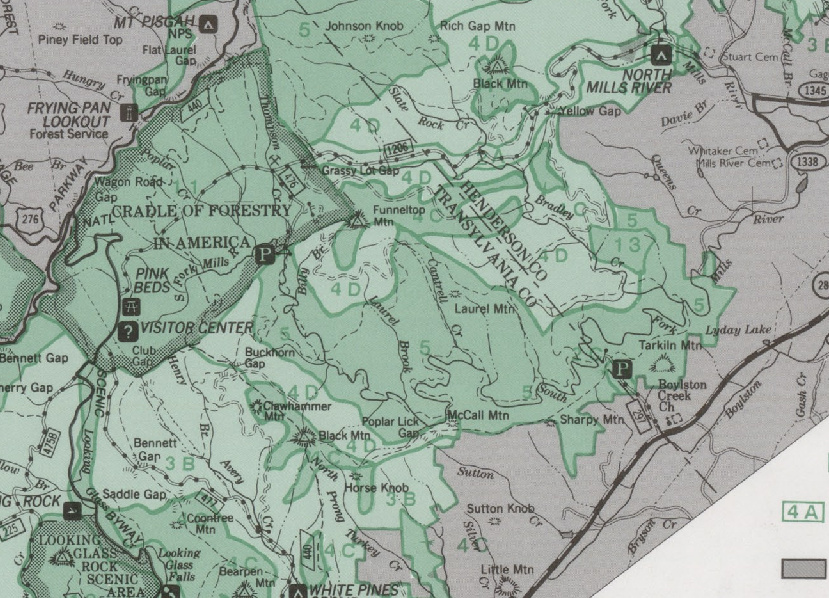

Why? Because the Forest Service’s draft maps of the new management areas showed much of that area as being “suitable for timber production” under Management Areas #1 and 2A in the proposed new plan.

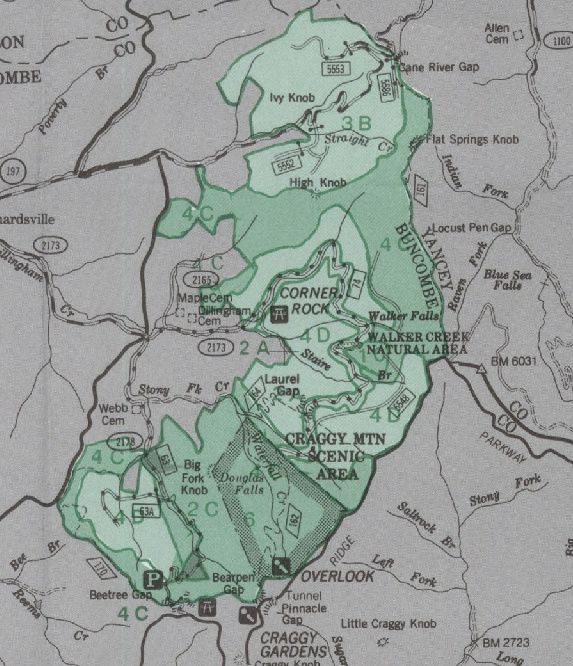

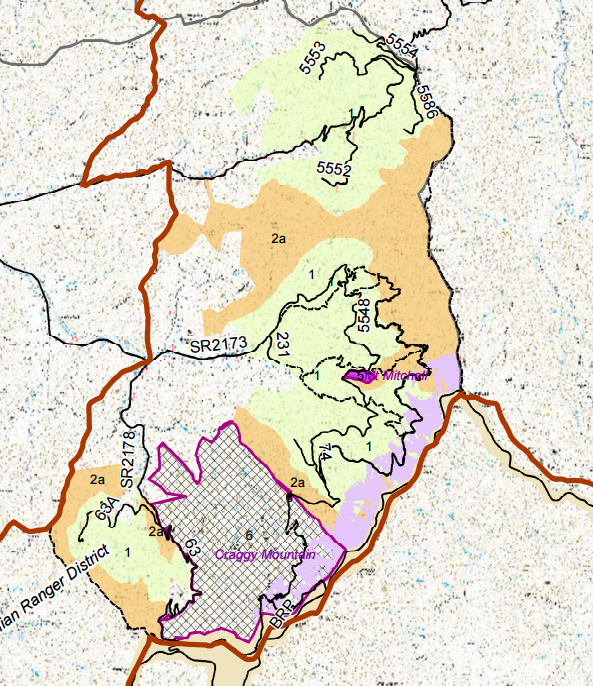

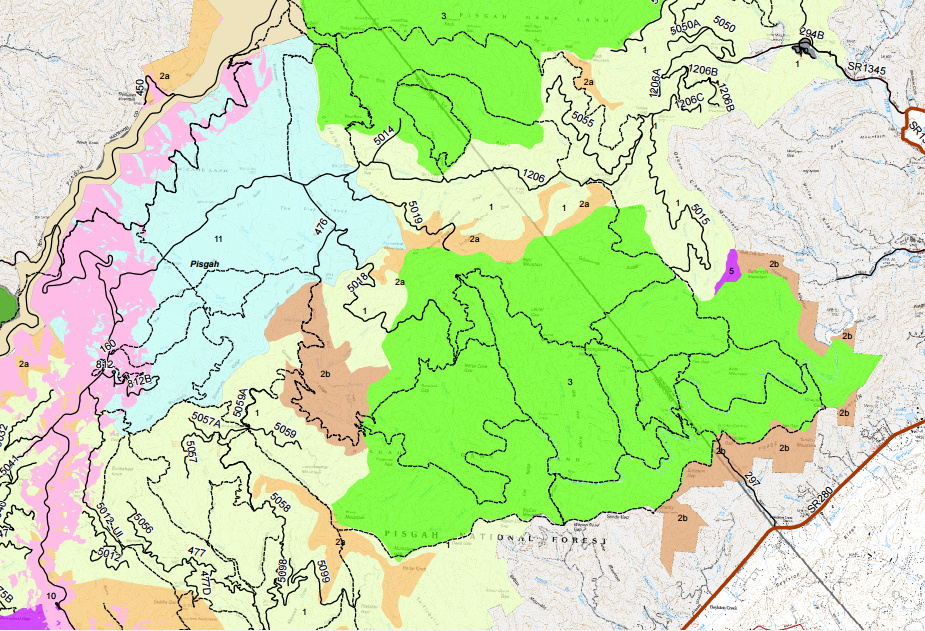

Here’s a couple of maps that show what I mean:

Under the new plan, all areas outside of the small, already-proposed-for-wilderness “Craggy Mountain Wilderness Study Area” have a definitive YES in the “Suitable for Timber Production” column. Something people who love the Big Ivy area – and understand its vitally important position in biodiversity and its overall uniqueness in the southern Appalachian mountain ecosystem – could hardly stand by.

Despite the Forest Service’s insistence that there were “no plans to log Big Ivy” at that time, it wasn’t lost on the crowd that – per the proposed management areas they were showing us – they were leaving wide open the possibility to make such plans in the future if they so chose. After all, large-scale logging had already happened there as recently as the late 80’s, leaving large, ugly scars on the landscape, some of which are visible still from the Blue Ridge Parkway.

And with the expansion of the Craggy Mountain Wilderness area to include the Douglas Falls area, that prevents the kind of signage, blazing, and mechanical trail maintenance which makes the hike to the popular waterfall possible for families and kids.

Since that Big Ivy meeting, the Forest Service has called for a “reset” in its engagement with the public, saying there was much misunderstanding in the initial rounds of discussions in 2014 and early 2015. The public input has since largely reorganized away from individual contributions and re-formed in the shape of behind-the-scenes meetings with representatives from what amounts to political and lobbying groups for the purposes of this process with the goal of coalescing power to push harder on central ideas. And generate less fuss. But, at least to individuals interested in the process like myself, it’s been nothing but crickets on whether they would consider changing the base management area designations they shared with us last fall.

So logging could again be coming soon to a forest near you!

Or maybe not?

Potential Wilderness

At the current stage in the plan-making process, the Forest Service is required by law to evaluate which areas could (maybe, possibly) be included in the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS). If added to the system, those lands will be forever protected from logging, road building, and of course “fracking”. They’re touting it as the chance to re-engage with the public, hold open meetings for interested individuals, and once again solicit our input about those Places We Want To Save. As many of the articles regarding the Wilderness evaluation have been trumpeting, “Now’s our Chance”!

…Or is it?

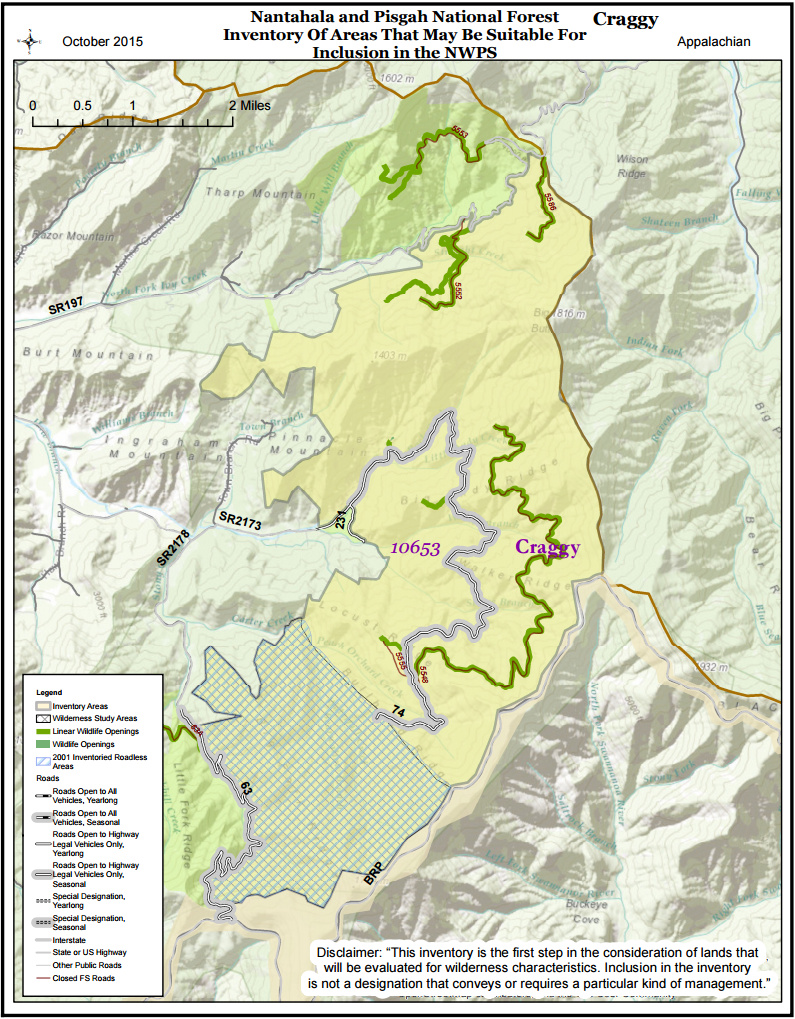

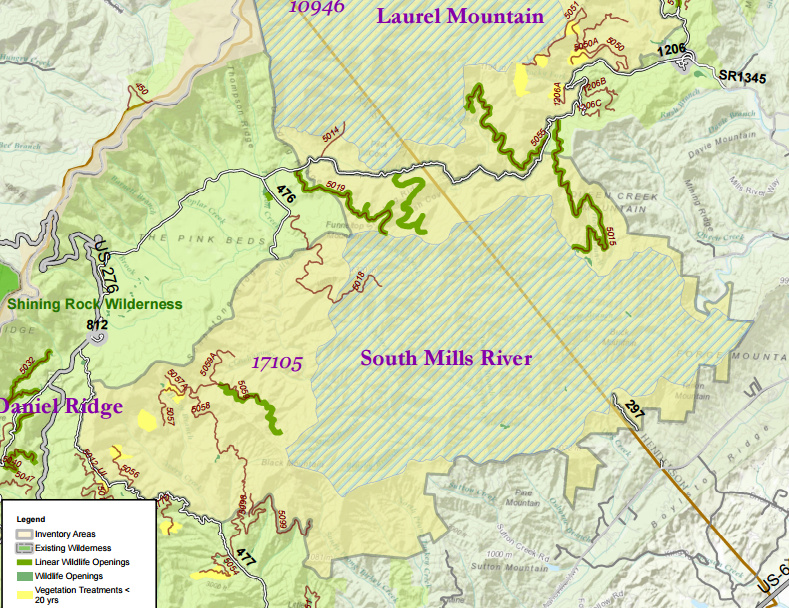

The Forest Service has created an “inventory” of land potentially suitable to be called Wilderness: the Big W. Any lands coming even close to meeting the legal requirements for Wilderness are in the inventory; they’ve cast a very wide net.

Nearly all of Big Ivy is in it; the South Mills River Backcountry is in it, as are many other other important areas of Pisgah and Nantahala National Forests.

And, separately, the South Mills River itself (and other rivers and streams) are up for potential Wild and Scenic River status, a blessing which confers its own special set of protections to the waterway, its tributaries, and the lands adjacent to them.

Once the Forest Service has listened patiently to us all cheer and/or complain – we have until December 15, 2015 to speak up and send them our comments – they’ll take what we’ve said and the data they have gathered on their own back behind closed doors to the Analysis phase of the plan-making process, to whittle down the areas that qualify for The Big W. according to the strictest interpretation of the law.

If any areas make it through unscathed, they’ll be recommended for Wilderness in the new plan; it’ll then literally take an act of Congress to make the Big W. status official for any such recommended areas.

The key here, however, is that whatever doesn’t make the cut appears to fall right back to the Management Area that gets proscribed by the new Plan. This hasn’t been explicitly stated, and keeps getting glossed over in the recent wider discussion, but I see nothing to indicate that a mere pass through the Wilderness inventory has any effect whatsoever on lands that don’t get full recommendation.

So as far as I can tell, those fall back under Management Areas like #1, which were described like this in the old 1994 plan amendment:

Emphasizes sustainable supply of timber products and motorized access into the forest for traditional forest uses.

Perhaps more has been divulged to the special interest group leaders behind closed doors.

Frankly, I’m sure a lot of the folks in the collaborative group – who were way outnumbered in every truly public meeting I ever attended, I might add – want to see expanded logging take place anyway. And weirdly, it’s being pitched as a battle between “sportsmen”, who want to see more logging, and “environmentalists”, who want everything declared Wilderness so it can never be touched.

Ultimately, what’s being widely celebrated on the environmentalists’ side as a chance for us to show our support for protection of the area’s vital forest resources starts to sound like much less of a sure thing, with the requirements for wilderness being so strict and the default management areas underlying the evaluation areas being so logging-friendly.

And to complicate things even further is what becomes of any lands that do get designated as Wilderness. Despite it’s protections against logging and other extractive uses, it’s certainly not a non-controversial designation in its own right. Because Wilderness is A Big Deal. Once an area is Wilderness, all bets are off. It means no more trail signs or blazes. It means little to no more trail maintenance or construction. Bikes are banned; groups of a large size are prohibited. Any and all mechanical transportation or equipment is prohibited.

It becomes a Truly Wild Place, enshrined in law.

Forget the “sportsmen” who might want some intact, healthy forests in which to “sport”, and in which their sport is not outlawed! I’m talking mountain bikers here, of course.

(Don’t get me wrong: I’m not against logging or forest products in general. And much of Pisgah and Nantahala is perfectly appropriate for it. The North Mills River project, for example, seems to have been well executed in a no-one-thinks-this-is-wilderness setting. It’s just icky to imagine logging in certain parts of Pisgah — the parts which largely coincide with the Wilderness inventory areas, and which are simply not your run of the mill patches of woods. A bit of “not in my back forest” syndrome, I’d have to admit).

Many areas not far from our hike (which I’m about to get back to, I promise!), like Daniel Ridge and Cedar Rock Mountain, as well as those in other parts of the forest like Bluff Mountain are also proposed to be put in the same, new, logging-friendly Management Areas numbered 1 and 2 if they don’t cut the mustard for Wilderness. All of which are places where many forest users I know could hardly fathom a large-scale logging project taking place, but need look no further than, say, Courthouse Creek or North Mills River to see one in action or just completed, respectively.

Or Something Else?

So The Big W. is a thorny issue. Is there an alternative that gives these special places the protection they deserve without all that goes with it?

As a matter of fact, there is! Several, in fact. An example from the 1994 amendment to the current plan:

MA 5: Provide large blocks of forest backcountry with little evidence of human activities. No timber management.

Well, ok. Sweet! The description above is for the Backcountry management area designation (#5 in the 1994 plan, or #3 in the proposed new plan). (There are other Management Area designations which have more specific purposes that could work, too.) And the South Mills River, the locale of our hike, is not currently open to large-scale logging, because it is already a designated Backcountry area. The forest there is “managed” (minimally) to near-wilderness standards, but without all the dang restrictions.

Best of all, it requires no act of Congress to put one of those alternative Management Areas in place – only a change to those proposed base management areas maps to fit in with the new plan.

But again, the Forest Service isn’t officially taking comment on such changes anymore, and they have made no indication if the comments and controversy that came in almost a year ago had any influence whatsoever. I get the uneasy feeling — and I hope I’m wrong — that they’re hiding under a “see the new areas that could become Wilderness!” veil when conversing with us average peons just to quell some of the controversy, all the while knowing full well that most of those areas will not get recommended for Wilderness and remain open to logging. And while the real negotiating takes place out of sight.

Signs of Logging

Now on to the rest of our trip report!

Remember, one of the reasons I chose this place for our hike was to get a better sense of what kind of forest the Backcountry management area results in, and what an Inventoried Potential Wilderness Area looks like for when I submit my comments to the Forest Service.

After crossing the bridge, we started up South Mills River trail, which initially climbs a low ridge above the river. It’s an old logging road, as are many of the trails in Pisgah. Just before the trail started descending again, we veered right on the Mullinax “trail”, uphill, on another old logging road. That continues its journey up the young ridge, which eventually grows up into something called Poundingstone Mountain farther to the northwest.

Old roads go off in every direction at junctions, hearkening back to the days when extinct species of ‘dozers roamed these hills, carving out the routes by which the virgin logs could be forcibly extracted and sent out to the highest bidder.

The trail cuts across a cove which sports a bold stream (at least during periods of wet weather like we’ve had). It then veers right onto another logging road, which goes into the cove and follows the stream up to its source. It’s only at the head of this cove does the trail stop looking like an old road, where it turns into purpose-built singletrack for a bit.

We continued hiking up and over the low ridge through a series of switchbacks, closed in by rhododendron and mountain laurel along much of the way.

The Mullinax trail then descends on a winding path through some patches of dead Eastern Hemlock trees to meet up with the Squirrel Gap trail south of Mullinax Gap. From there, which appears to be an old home site of some sort since there is another clearing, we continued onto the Squirrel Gap trail – past a huge bulldozer-mound of dirt, I might add – onto what is considered one of the finest trails for hiking and mountain biking in all of Pisgah.

The great Squirrel Gap is a purpose-built, narrow, winding singletrack trail which starts just northeast of where we picked it up. And here’s where you can start to see how this area just might qualify for Wilderness. The trees get larger; there are fewer signs of logging up there. The forest closes in, yet at the same time, vistas of forlorn ridges across deep valleys appear off to the sides of the trail.

Deep piles of freshly fallen leaves nearly obscure the trail itself, leaving visible only a slightly less-steep ledge cutting along the mountainside – and the occasional blaze – for hikers or mountain bikers to follow. It’s beautiful. The mountain environment here isn’t particularly noteworthy but the sounds of civilization have disappeared. Even the sounds of the river have faded, leaving only the whispering breeze through the last of the (surprisingly still green) autumn leaves clinging to the bare branches.

For one good 15 minute span of time, where we stopped to relax at the Poundingmill trail junction, I didn’t even hear an airplane.

Our hike veered left, south, and sharply downhill here. We eeked our way into a cove forest where tall trees stood like toothpicks lined up on the steep slopes of the mountainside. A remarkable rounded lump of terrain contained entirely within the valley below was the destination for the trail, which wound across its top before dropping off the left side and crossing the very beginnings of Poundingmill Branch. One could almost be convinced that they were in a wild place, at a different time, as they descended this old path.

But then, someone is coming. It’s a jogger, out for a quick afternoon jaunt from the Turkeypen trailhead, heading in the opposite direction as we are, uphill. Seemingly unfazed running up the same slope I just had a non-zero amount of trouble walking down. A quick run; only about 9 miles, she said. Should be done in a couple of hours, she said. In addition to making me feel out of shape, our chat reminds me just how close to the trailhead we still are. I expected us to be back in less than an hour myself.

And then, the trail merges in with another old logging road, vanquishing any remaining notion that this is truly Wilderness. It crosses yet another road that I happen to know secretly leads back to the Mullinax trail, and this one’s covered in bike tracks. We were now on the portion of Poundingmill trail I’d already hiked before.

We made our way down the final stretch, through sections overgrown so thickly by doghobble you could hardly tell there was still a trail save for the blazes and ancient rusty signs proclaiming “HIKER TRAIL”. The path ends abruptly on the South Mills River “trail” (wide old road), with the crystal-clear rushing river just on the other side.

From there, it’s an easy, beautiful walk downstream past a couple of bends in the rushing river back to the one hill and the Mullinax junction, where the loop part of our hike ended. We pass a large campsite filled with tents, and a dozen or so folks hanging out and getting ready for what’s to be a fairly chilly night. We pass even more folks – groups of 10 or more – heading out as we approach the trailhead.

For us, it’s back across the suspension bridge, up the logging road connector, and back in the car, zipping off for dinner in downtown Asheville in not much time at all.

Our Evaluation

When I look back on this hike, it’s hard for me to get the sense that I was ever truly “out in the Wilderness”, although parts of it did feel relaxing and remote. All of it exudes elements of a delicately balanced ecosystem; special and – despite past evidence of human interference – even pristine. Even on a very busy day, after taking the Mullinax trail, we encountered only one other person until we were nearly back at the trailhead. The crowds do tend to stick very close to the parking lot.

At no point up to the Squirrel Gap junction does it really feel like you’re in the Wilderness. It’s a remote enough area, for sure, but there are signs of logging everywhere: gates, wide old roads, a clearing in the forest here, a patch of skinny young trees there.

I do know from experience that even further along Squirrel Gap trail past where we turned off onto Poundingmill, near Cantrell Creek, it starts to feel a lot more remote than the parts we hiked. But Wilderness?

It crossed my mind more than once that these features of a logged-out, yet healing, forest are not the types of things the very specific federal law considers favorable to a Wilderness designation. In fact, it is for these reasons I am skeptical that South Mills River would even meet the rather high bar for recommendation.

Without telling her why I chose the hike — other than it meeting our time and exercise requirements for that day — I asked my wife what she thought about it. Was it a Wilderness hike, in her opinion? Her response:

No, not really. We weren’t doing any bushwhacking; the trail was in good condition. I mean, it was very quiet, and peaceful. But I think of wilderness as really having to hack your way through on a trail that’s not in good shape. That trail was well maintained.

Now the South Mills River itself is a beautiful, pristine, free-flowing river which deserves as much protection as it can get, seeing as it’s one of the drinking water sources for the Asheville & Hendersonville municipal areas. I could totally get on board with a Wild and Scenic designation for it.

And a very big part of me wants to see these other areas – those same inventoried areas mentioned above – to become more protected, to prevent the rapacious logging and mining and other extractive activities the Forest Service deems one of the “many uses” the lands under its purview are suitable for. However, it bugs me that the Wilderness designation and all of its restrictions, along with its low chance of actualization, is the only thing they’re currently taking comments on.

Whereas, the Backcountry designation feels totally appropriate for nearly all of those same areas. I’ve hiked and biked in all of them, and while there is certainly evidence of human activity it is “little”; the scars left by logging are mostly smoothed over and healing quickly, with few exceptions.

Those places feel like backcountry. They do not quite feel like wilderness.

I get that for the huge, truly wild and hairy places like Shining Rock which have been Wilderness for decades anyway, the restriction Wilderness conveys make sense. I certainly value being able to get that experience there. But for places like South Mills River, an area that is enjoyed by a such a wide variety of people in a successful manner like it is now, I don’t like the thought of applying those draconian rules.

But the Forest Service has yet to officially ask for comment from the public on the management areas other than Wilderness. They have the power; it’s just not clear if and how they’ll exercise it.

For what it’s worth, I will be submitting my comment to the Forest Service against recommending the South Mills River area (and the others mentioned here) as a new Wilderness. It should stay exactly as it is: Backcountry. And I will support reclassification of the base management areas to “at least” Backcountry (or something more appropriate, yet similarly protective) for all of the areas added to the Wilderness inventory.

Incidentally, the areas I feel strongly about, and which made the Wilderness inventory, coincide well with the areas identified by The North Carolina’s Mountain Treasures project, and I generally agree with their comments. I may be using their talking points — they are one of the few organizations supporting “at least Backcountry” like I do for the areas that don’t make Wilderness — as a template for my own comments.

(Exception: Lost Cove, near Wilson Creek, totally feels like Wilderness to me an I would support its designation as such. That place is wild. Some will, of course, disagree with me on that).

Nevertheless, I look forward to being able to have the same experience here in the future as I did that weekend in November 2015 – except maybe on my bike next time. If I so choose.

I’ll publish the comments I submit to the Forest Service in a separate post and I encourage you to comment here, comment to the Forest Service, comment anywhere it makes a difference. Because this new plan is going to be in force for a long time, with wide consequences for the future of the places we love, like South Mills River.

[map style=”width: 100%; height: 400px;” gpx=”/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/2015-11-14-Turkeypen-Mullinax-Squirrel-Gap-Pounding-Mill-South-Mills.gpx”]

Butch Greene

F.S. bulldozed Big Ivy last week.